Metaphors mold minds

March 2022

You can watch the 15 minute version of this talk here.

Every good design is founded on a great metaphor.

Music to your ears? Or did that go in one ear and out the other. Actually, those metaphors are terrible. Nothing more than stock phrases, recited daily to obfuscate the real meaning of our conversations.

Metaphor driven design is different. It’s about the other sort of metaphors, the rich world of visual imagery that’s critical to our understanding of novel interactions.

Recall the confusion surrounding Tesla’s “self-driving” rollout, or the backlash against early dockless bike schemes. When you introduce a radically new interaction there’s often a high risk of failure. These failures stem from a mismatch between the understanding of the users and the intent of the designers. I’m going to show you why this happens, and how metaphors can help fix it.

Aside: apologies in advance to any linguists for the inevitable mix ups between metaphors, analogies, idioms, allegories and similes. Design is hard, but grammar is harder.

What does electricity smell like?

The European EV market is well past early adopter mode, yet for most people the very act of putting electricity into a car remains an alien concept.

Filling up a car with petrol brings a cacophony of familiar experiences: the cold of the nozzle, the smell of the fuel, the sound of the pump, the vibrations beneath your hand. All this feedback comes for free from the natural physics of that wet, heavy liquid flowing through the pipe.

Charging an electric car couldn’t be more different. You reach across, take the charging gun, plug it into your car and ... ... ... silence.

What does electricity sound like? Smell like? How does it move? Designing an EV charger is not just a brand or UX challenge. Our brief is to design the very sensation of moving electricity from one place to another.

Is electricity like water, flowing down the hose in a succession of marching blue lights? Or is it a wild machine that hums and whirls, vibrating with the energy of charging from side to side?

Perhaps the metaphor we choose could be a little more human. The polite charging butler, who gently offers out the charging gun as you pull alongside. Or the tired old man charger, his head bowed slightly as he slumps forward, kilowatt after kilowatt, after a hard day’s work

Designing beyond our users

From bikes to cars to drones, designing for future mobility has a particularly unique interaction challenge.

As designers we obsess over understanding our users: finding, profiling, co-creating and testing with them. Yet the vast majority of people who encounter our products are not users of these products. Far more pedestrians will interact with our autonomous car or shared e-bike scheme than the very few who ride or drive in them. We can't hope to design an inclusive city environment unless they believe in our ideas too.

These “non-users” are a nightmare to design for. Without onboarding or curated storytelling to explain what’s going on, we simply thrust an object in front of them and hope for a positive reaction. In the worst case, our products quickly move from vital city infrastructure to the bottom of the River Seine.

“Does not want to throw it in the river” should be on everyone’s design brief. But to understand what went wrong, we must begin with the relationship we have with these bikes or scooters. Responsibility stems from a feeling of ownership, but the important question here is who owns them emotionally, not legally.

As a daily commuter, how do I think of these vehicles. My private, two-wheeled chauffeur? A limitless supply of throwaway machines, like grabbing a water bottle in a marathon and discarding it seconds later? Or perhaps they’re more like a stray cat outside my door. An animal that I care for but who isn’t ultimately my responsibility.

Fundamentally, without a clear mental model for our relationship with this service, we’re unsure how to act. Into this void we all pour our own, diverse interpretations. All of these interpretations clash and conflict, and the result is self-evident.

To fix this, we must define the right metaphor for the interaction up front, and then allow that metaphor to consistently permeate through everything: the product, service, digital experience, marketing and brand.

The best metaphors are remixers

Good metaphors are novel, relatable, and original.

But the best metaphors are remixers. They start with a simple idea and twist it to create something new. The more edgy, bold or humorous the twist, the more it will stick.

The world of fantasy provides a rich source of ideas for metaphors. It enables us to express concepts that we lack everyday language for. Imagine building an e-bike system that switches on when your phone attaches to the handlebar cradle. Is this a plastic phone clip, or Iron Man’s artificial heart, bringing the intelligence and life the moment it drops into place?

Not every metaphor need come with a fantasy connection. Characterisation is a great way to build relatable metaphors. Recall the lonely e-scooter outside your door that you care for like a stray pet, or the EV charging station that’s reached its maximum loading, like an old man tired out after a hard day’s work.

One of the most common metaphor remixers is X-for-Y. It’s so common that it’s often carried through to product marketing, think “Whatsapp for your toaster” or “Tinder for dogs”. X-for-Y is especially powerful with recognisable brand names, abusing their stereotypes for maximum effect. These are the metaphors that you really remember.

The more novel your interaction, the more strongly grounded it needs to be in a clear and consistent metaphor which guides the behaviour of the people who use it.

This is metaphor driven design. You can design with metaphors at any stage of a design project, but there are three places where they bring the most value:

- Defining a vision

- Defining a relationship

- Designing product details

Let’s take a look.

Hagrid, but with a bit of Catwoman

Thinking in metaphors is particularly helpful for those in your team who wouldn’t call themselves a designer. Metaphors bring a small but comforting level of abstraction that helps stakeholders tease out the vision for a company’s future.

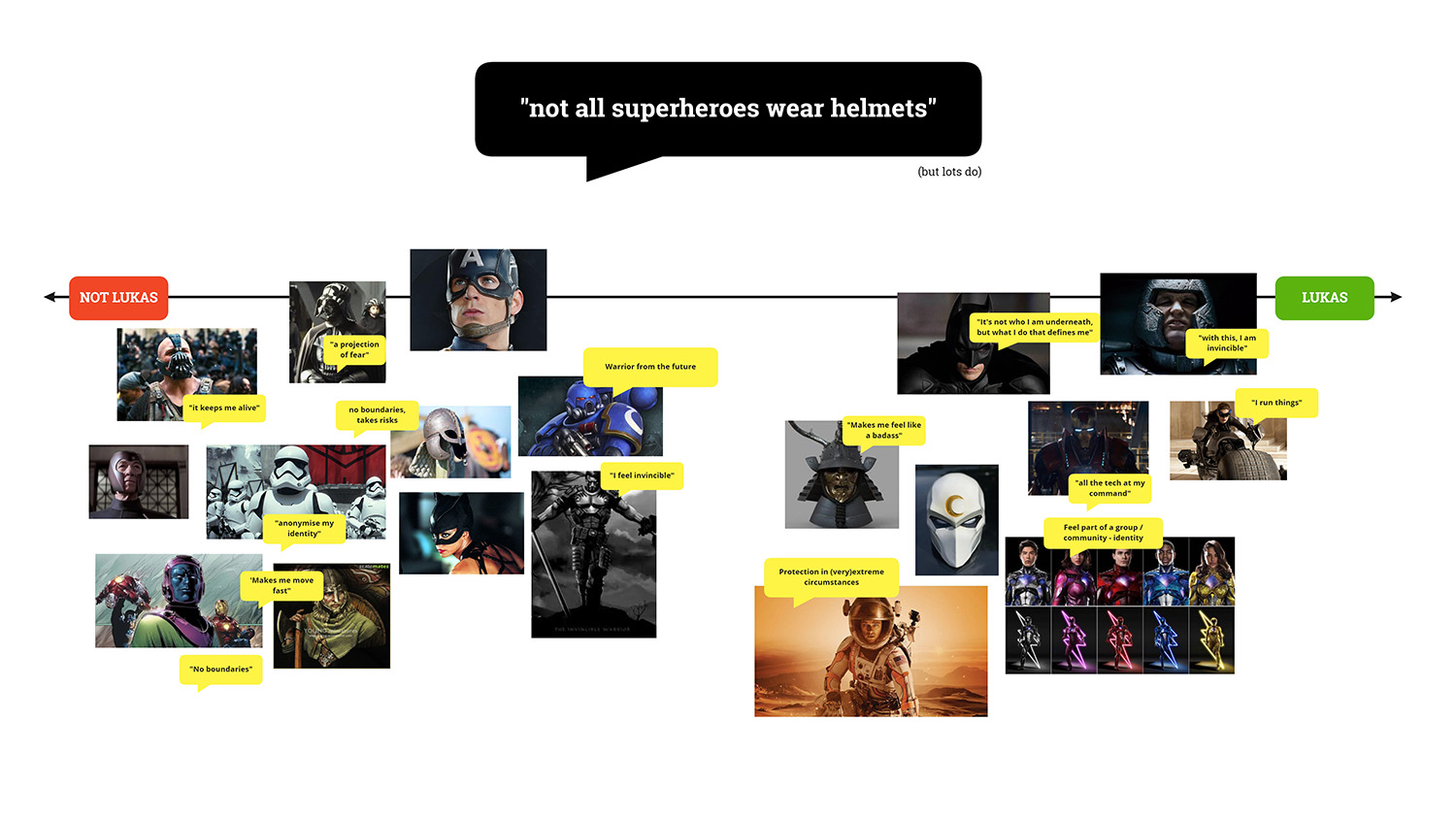

In one example, the brand made safety helmets, but we started with superheroes. Not all superheroes wear helmets, but actually a lot do. The different mentalities of each superhero helped frame the way customers relate to the products, moving very quickly from “we think” to “users think”.

Who wears a helmet for both the feeling of protection and freedom? We would start sentences like “it should be Captain America, but with a little bit more menace like Batman”. Intangible ideas suddenly felt a lot more relatable.

The showfolk of the streets?

In London, Brompton bicycles are extremely popular. Fold it down, carry it on the tube, unfold and off you zip. There’s a joke that people only speak to each other on the Underground for three reasons: a dog, a baby, or a Brompton.

The thing is, people don’t typically unfold a Brompton. They unfold it. A dramatic flourish that cries Hello! My Brompton is here!

So it’s fun to ask a Brompton owner how they perceive their interaction with the bike.

Are they the showfolk of the city, master entertainers lined up in Covent Garden alongside jugglers and street artists with a highly honed performance routine? Or perhaps Bromptons are the Nimbus 2000, Harry Potter’s famous (but still widely available) broom for Qudditch. Nimble and agile, hop on and off as you go around the London backstreets.

Good guesses, but no. Ask someone in a bar, with their Brompton folded away in the corner, and they’ll probably say its more like taking your dopey Labrador to the pub. Every 30 seconds you glance across, nervously thinking “is he still there?”, “has he wandered off somewhere yet?”.

This is really key. Defining and designing against a metaphor is one thing but it needs to match with people’s expectations. The key is to create consistency, a guiding metaphor ensures you don’t build a relationship based on one idea only to break it with something very tangential.

Deliveroo for drugs

Today, countries like Ghana and Rwanda lead the way in delivering medical equipment via drones. But there’s also immense potential in very congested cities across the world, including London.

Last year I worked with one of the service operators in the UK. Nobody has ever seen a medical drone fly through their city. So the question we kept asking was: what is this going to feel like? How can we explain the concept of rapid, point-to-point medical supply delivery?

We needed a strong metaphor to help make sense of it all. Butlers with bandages? A fleet of toy Fedex planes? Owl delivery from Harry Potter? Deliveroo for drugs?

Deliveroo for drugs is particularly evocative because in the UK, the bicycle food courier Deliveroo is so omnipresent. Once this metaphor is defined, it cascades through and defines the behaviours and interactions that follow. Does the drone have cameras? Do I mind that it has cameras? What colour is it? What sound does it make? Am I excited, relieved or terrified to see it flying past my window? If it crashes in my school field, how do I respond?

Define the metaphor and the rest can follow.

At ease in an unfamiliar world

Metaphor driven design is just a tool like any other. But for me, it’s an especially powerful one.

Think about the product or service you’re working on right now. What does it represent to people? How do your users and non-users understand it? Does the image in their minds match the relationship you’re trying to build?

The best metaphors are remixers. The metaphors we choose, and the images they create build a clear and consistent understanding, especially with very novel interactions and experiences. They help us design beyond our users, avoiding the chaos that comes when we all interpret something in our own, unique, human ways.

A strong metaphor puts people at ease in this wild and unfamiliar world.